Lightwood Philosophy

Introduction

Lightwood works by generating code for Predictor objects out of structured data (e.g. a data frame) and a problem definition. The simplest possible definition being the column to predict.

The data can be anything. It can contain numbers, dates, categories, text (in any language, but English is currently the primary focus), quantities, arrays, matrices, images, audio, or video. The last three as paths to the file system or URLs, since storing them as binary data can be cumbersome.

The generated Predictor object can be fitted by calling a learn method, or through a lower level step-by-step API. It can then make predictions on similar data (same columns except for the target) by calling a predict method. That’s the gist of it.

There’s an intermediate representation that gets turned into the final Python code, called JsonAI. This provides an easy way to edit the Predictor being generated from the original data and problem specifications. It also enables prototyping custom code without modifying the library itself, or even having a “development” version of the library installed.

Pipeline

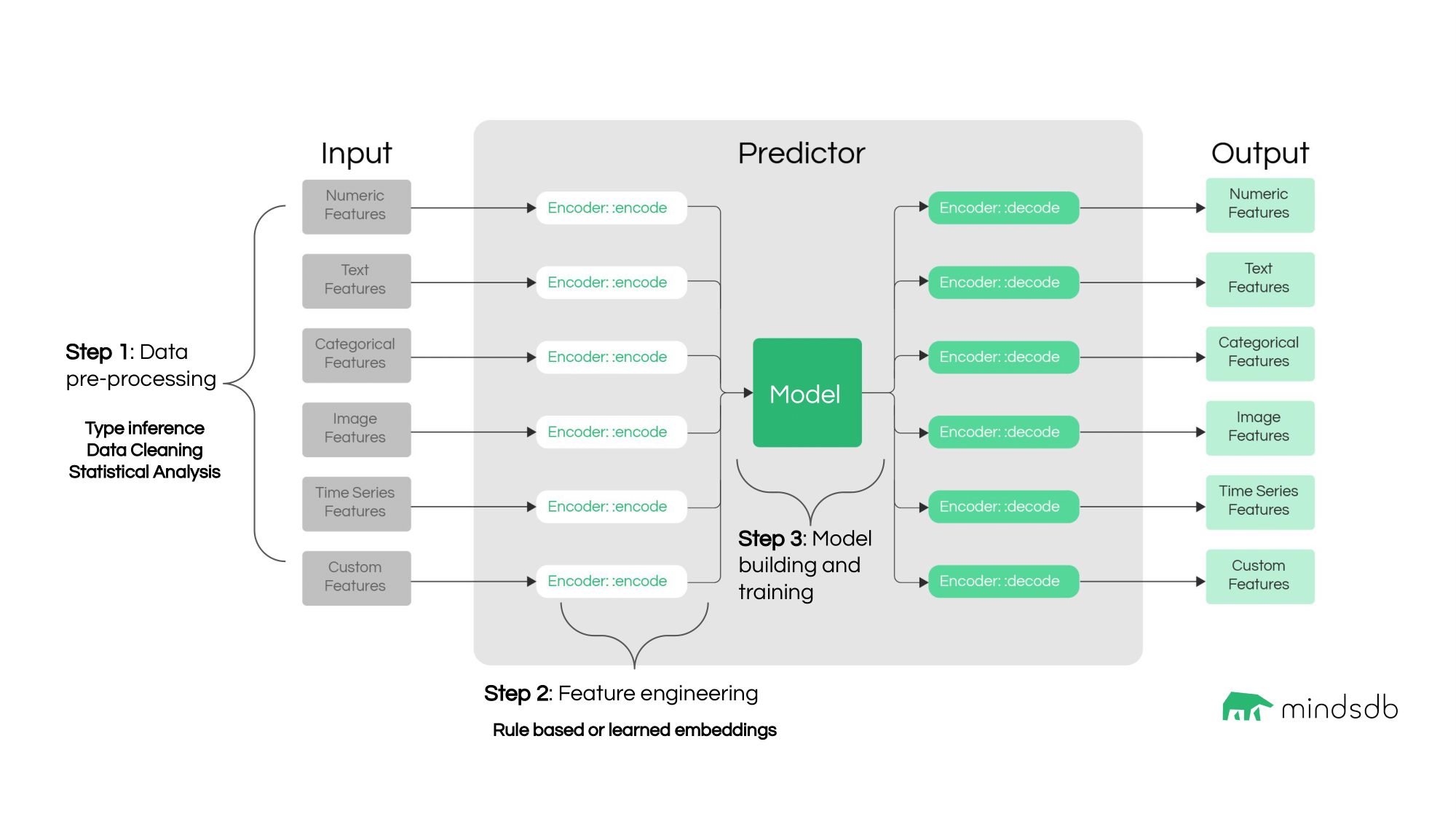

Lightwood abstracts the ML pipeline into 3 core steps:

Pre-processing and data cleaning

Feature engineering

Model building and training

By default, each of them entails:

i) Pre-processing and cleaning

For each column in your dataset, Lightwood will infer the suspected data type (numeric, categorical, etc.) via a brief statistical analysis. From this, it will generate a JsonAI object.

Lightwood will perform a brief pre-processing approach to clean each column according to its identified data type (e.g. dates represented as a mix of string formats and timestamp floats are converted to datetime objects). From there, it will split the data into train/dev/test splits.

The cleaner and splitter objects respectively refer to the pre-processing and the data splitting functions.

ii) Feature Engineering

Data can be converted into features via “encoders”. Encoders represent the rules for transforming pre-processed data into a numerical representation that a model can use.

Encoders can be rule-based or learned. A rule-based encoder transforms data per a specific set of instructions (ex: normalized numerical data) whereas a learned encoder produces a representation of the data after training (ex: a “[CLS]” token in a language model).

Encoders are assigned to each column of data based on the data type, and depending on the type there can be inter-column dependencies (e.g. time series). Users can override this assignment either at the column-based level or at the datatype-based level. Encoders inherit from the BaseEncoder class.

iii) Model Building and Training

We call a predictive model that intakes encoded feature data and outputs a prediction for the target of interest a mixer model. Users can either use Lightwood’s default mixers or create their own approaches inherited from the BaseMixer class.

We predominantly use PyTorch based approaches, but can support other models.

Multiple mixers can be trained for any given Predictor. After mixer training, an ensemble is created (and potentially trained) to decide which mixers to use and how to combine their predictions.

Finally, a “model analysis” step looks at the whole ensemble and extracts some stats about it, in addition to building confidence models that allow us to output a confidence and prediction intervals for each prediction. We also use this step to generate some explanations about model behavior.

Predicting is very similar: data is cleaned and encoded, then mixers make their predictions and they get ensembled. Finally, explainer modules determine things like confidence, prediction bounds, and column importances.

Strengths and drawbacks

The main benefit of lightwood’s architecture is that it is very easy to extend. Full understanding (or even any understanding) of the pipeline is not required to improve a specific component. Users can still easily integrate their custom code with minimal hassle, even if PRs are not accepted, while still pulling everything else from upstream. This works well with the open-source nature of the project.

The second advantage this provides is that it is relatively trivial to parallelize since most tasks are done per-feature. The bits which are done on all the data (mixer training and model analysis) are made up of multiple blocks with similar APIs which can themselves be run in parallel.

Finally, most of lightwood is built on PyTorch, and PyTorch mixers and encoders are first-class citizens in so far as the data format makes it easiest to work with them. In that sense performance on specialized hardware and continued compatibility is taken care of for us, which frees up time to work on other things.

The main drawback, however, is that the pipeline separation doesn’t allow for phases to wield great influence on each other or run in a joint fashion. This both means you can’t easily have stuff like mixer gradients propagating through and training encoders, nor analysis blocks looking at the model and deciding the data cleaning procedure should change. Granted, there’s no hard limit on this, but any such implementation would be rather unwieldy in terms of code complexity.